History

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: references need proper formatting; citations are missing (January 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Although contemporary professional use of the term 'urban design' dates from the mid-20th century, urban design as such has been practiced throughout history. Ancient examples of carefully planned and designed cities exist in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas, and are particularly well known within Classical Chinese, Roman and Greek cultures (see Hippodamus of Miletus).citation needed

European Medieval cities are often, and often erroneously, regarded as exemplars of undesigned or 'organic' city development.citation needed There are many examples of considered urban design in the Middle Ages (see, e.g., David Friedman, Florentine New Towns: Urban Design in the Late Middle Ages, MIT 1988). In England, many of the towns listed in the 9th century Burghal Hidage were designed on a grid, examples including Southampton, Wareham, Dorset and Wallingford, Oxfordshire, having been rapidly created to provide a defensive network against Danish invaders.citation needed 12th century western Europe brought renewed focus on urbanisation as a means of stimulating economic growth and generating revenue.citation needed The burgage system dating from that time and its associated burgage plots brought a form of self-organising design to medieval towns.citation needed Rectangular grids were used in the Bastides of 13th and 14th century Gascony, and the new towns of England created in the same period.citation needed

Throughout history, design of streets and deliberate configuration of public spaces with buildings have reflected contemporaneous social norms or philosophical and religious beliefs (see, e.g., Erwin Panofsky, Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism, Meridian Books, 1957). Yet the link between designed urban space and human mind appears to be bidirectional.citation needed Indeed, the reverse impact of urban structure upon human behaviour and upon thought is evidenced by both observational study and historical record.citation needed There are clear indications of impact through Renaissance urban design on the thought of Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei (see, e.g., Abraham Akkerman, "Urban planning in the founding of Cartesian thought," Philosophy and Geography 4(1), 1973). Already René Descartes in his Discourse on the Method had attested to the impact Renaissance planned new towns had upon his own thought, and much evidence exists that the Renaissance streetscape was also the perceptual stimulus that had led to the development of coordinate geometry (see, e.g., Claudia Lacour Brodsky, Lines of Thought: Discourse, Architectonics, and the Origins of Modern Philosophy, Duke 1996).

The beginnings of modern urban design in Europe are associated with the Renaissance but, especially, with the Age of Enlightenment.citation needed Spanish colonial cities were often planned, as were some towns settled by other imperial cultures.citation needed These sometimes embodied utopian ambitions as well as aims for functionality and good governance, as with James Oglethorpe's plan for Savannah, Georgia.citation needed In the Baroque period the design approaches developed in French formal gardens such as Versailles were extended into urban development and redevelopment. In this period, when modern professional specialisations did not exist, urban design was undertaken by people with skills in areas as diverse as sculpture, architecture, garden design, surveying, astronomy, and military engineering. In the 18th and 19th centuries, urban design was perhaps most closely linked with surveyors (engineers) and architects. The increase in urban populations brought with it problems of epidemic disease,citation needed the response to which was a focus on public health, the rise in the UK of municipal engineering and the inclusion in British legislation of provisions such as minimum widths of street in relation to heights of buildings in order to ensure adequate light and ventilation.citation needed

Much of Frederick Law Olmsted's work was concerned with urban design, and the newly formed profession of landscape architecture also began to play a significant role in the late 19th century.

Modern Urban Designedit

In the 19th century, cities were industrializing and expanding at a tremendous rate. Private business largely dictated the pace and style of this development. The expansion created many hardships for the working poor and concern for public health increased. However, the laissez-faire style of government, in fashion for most of the Victorian era, was starting to give way to a New Liberalism. This gave more power to the public. The public wanted the government to provide citizens, especially factory workers, with healthier environments. Around 1900, modern urban design emerged from developing theories on how to mitigate the consequences of the industrial age.

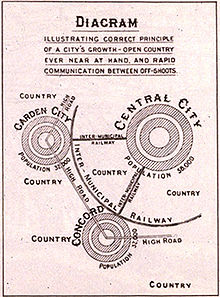

The first modern urban planning theorist was Sir Ebenezer Howard. His ideas, although utopian, were adopted around the world because they were highly practical. He initiated the garden city movement in 1898 garden city movement. His garden cities were intended to be planned, self-contained communities surrounded by parks. Howard wanted the cities to be proportional with separate areas of residences, industry, and agriculture. Inspired by the Utopian novel Looking Backward and Henry George's work Progress and Poverty, Howard published his book Garden Cities of To-morrow in 1898. His work is an important reference in the history of urban planning. He envisioned the self-sufficient garden city to house 32,000 people on a site 6,000 acres (2,428 ha). He planned on a concentric pattern with open spaces, public parks, and six radial boulevards, 120 ft (37 m) wide, extending from the center. When it reached full population, Howard wanted another garden city to be developed nearby. He envisaged a cluster of several garden cities as satellites of a central city of 50,000 people, linked by road and rail. His model for a garden city was first created at Letchworth and Welwyn Garden City in Hertfordshire. Howard's movement was extended by Sir Frederic Osborn to regional planning.

In the early 1900s, urban planning became professionalized. With input from utopian visionaries, civil engineers, and local councilors, new approaches to city design were developed for consideration by decision makers such as elected officials. In 1899, the Town and Country Planning Association was founded. In 1909, the first academic course on urban planning was offered by the University of Liverpool. Urban planning was first officially embodied in the Housing and Town Planning Act of 1909 Howard's ‘garden city’ compelled local authorities to introduce a system where all housing construction conformed to specific building standards. In the United Kingdom following this Act, surveyor, civil engineers, architects, and lawyers began working together within local authorities. In 1910, Thomas Adams became the first Town Planning Inspector at the Local Government Board and began meeting with practitioners. In 1914, The Town Planning Institute was established. The first urban planning course in America wasn’t established until 1924 at Harvard University. Professionals developed schemes for the development of land, transforming town planning into a new area of expertise.

In the 20th century, urban planning was forever changed by the automobile industry. Car oriented design impacted the rise of ‘urban design’. City layouts now had to revolve around roadways and traffic patterns.

In June 1928, the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM) was founded at the Chateau de la Sarraz in Switzerland, by a group of 28 European architects organized by Le Corbusier, Hélène de Mandrot, and Sigfried Giedion. At the CIAM was one of many 20th century manifestos meant to advance the cause of "architecture as a social art".

Team X was a group of architects and other invited participants who assembled starting in July 1953 at the 9th Congress of the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM) and created a schism within CIAM by challenging its doctrinaire approach to urbanism.

In 1956, the term “Urban design” was first used at a series of conferences hosted by Harvard University. The event provided a platform for Harvard's Urban Design program. The program also utilized the writings of famous urban planning thinkers: Gordon Cullen, Jane Jacobs, Kevin Lynch, and Christopher Alexander.

In 1961, Gordon Cullen published The Concise Townscape. He examined the traditional artistic approach to city design of theorists including Camillo Sitte, Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin. Cullen also created the concept of 'serial vision'. It defined the urban landscape as a series of related spaces.

In 1961, Jane Jacobs published ' The Death and Life of Great American Cities. She critiqued the Modernism of CIAM (International Congresses of Modern Architecture). Jacobs also claimed crime rates in publicly owned spaces were rising because of the Modernist approach of ‘city in the park’. She argued instead for an 'eyes on the street' approach to town planning through the resurrection of main public space precedents (e.g. streets, squares).

In the same year, Kevin Lynch published The Image of the City. He was seminal to urban design, particularly with regards to the concept of legibility. He reduced urban design theory to five basic elements: paths, districts, edges, nodes, landmarks. He also made the use of mental maps to understanding the city popular, rather than the two-dimensional physical master plans of the previous 50 years.

Other notable works:

Architecture of the City by Aldo Rossi (1966)

Learning from Las Vegas by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown (1972)

Collage City by Colin Rowe(1978)

The Next American Metropolis by Peter Calthorpe(1993)

The Social Logic of Space by Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson (1984)

The popularity of these works resulted in terms that become everyday language in the field of urban planning. Aldo Rossi introduced 'historicism' and 'collective memory' to urban design. Rossi also proposed a 'collage metaphor' to understand the collection of new and old forms within the same urban space. Peter Calthorpe developed a manifesto for sustainable urban living via medium density living. He also designed a manual for building new settlements in his concept of Transit Oriented Development (TOD). Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson introduced Space Syntax to predict how movement patterns in cities would contribute to urban vitality, anti-social behaviour and economic success. 'Sustainability', 'livability', and 'high quality of urban components' also became commonplace in the field.

Current Trendsedit

Today, urban design seeks to create sustainable urban environments with long-lasting structures, buildings, and overall livability. Walkable urbanism is another approach to practice that is defined within the Charter of New Urbanism. It aims to reduce environmental impacts by altering the built environment to create smart cities that support sustainable transport. Compact urban neighborhoods encourage residents to drive less. These neighborhoods have significantly lower environmental impacts when compared to sprawling suburbs. To prevent urban sprawl, Circular flow land use management was introduced in Europe to promote sustainable land use patterns.

As a result of the recent New Classical Architecture movement, sustainable construction aims to develop smart growth, walkability, architectural tradition, and classical design. It contrasts from modernist and globally uniform architecture. In the 1980s, urban design began to oppose the increasing solitary housing estates and suburban sprawl. Managed Urbanisation with the view to making the urbanising process completely culturally and economically and environmentally sustainable, and as a possible solution to the urban sprawl, Frank Reale has submitted an interesting concept of Expanding Nodular Development (E.N.D.) that integrates many urban design and ecological principles, to design and build smaller rural hubs with high-grade connecting freeways, rather than adding more expensive infrastructure to existing big cities and the resulting congestion.

Paradigm Shiftsedit

Throughout the young existence of the Urban Design discipline, many paradigm shifts have occurred that have affected the trajectory of the field regarding theory and practice. These paradigm shifts cover multiple subject areas outside of the traditional design disciplines.

- Team 10 - The first major paradigm shift was the formation of Team 10 out of CIAM, or the Congres Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne. They believed that Urban Design should introduce ideas of ‘Human Association’, which pivots the design focus from the individual patron to concentrating on the collective urban population.

- The Brundtland Report and Silent Spring - Another paradigm shift was the publication of the Brundtland Report and the book Silent Spring by Rachel Carson. These writings introduced the idea that human settlements could have detrimental impacts on ecological processes, as well as human health, which spurred a new era of environmental awareness in the field.

- The Planner's Triangle - The Planner's Triangle, created by Scott Cambell, emphasized three main conflicts in the planning process. This diagram exposed the complex relationships between Economic Development, Environmental Protection, and Equity and Social Justice. For the first time, the concept of Equity and Social Justice was considered as equally important as Economic Development and Environmental Protection within the design process.

- Death of Modernism (Demolition of Pruitt Igoe) - Pruitt Igoe was a spatial symbol and representation of Modernist theory regarding social housing. In its failure and demolition, these theories were put into question and many within the design field considered the era of Modernism to be dead.

- Neoliberalism & the election of Reagan - The election of President Reagan and the rise of Neoliberalism affected the Urban Design discipline because it shifted the planning process to emphasize capitalistic gains and spatial privatization. Inspired by the trickle down approach of Reaganomics, it was believed that the benefits of a capitalist emphasis within design would positively impact everyone. Conversely, this led exclusionary design practices and to what many consider as “the death of public space”.

- Right to the City - The spatial and political battle over our citizens rights to the city has been an ongoing one. David Harvey, along with Dan Mitchell and Edward Soja, discussed rights to the city as a matter of shifting the historical thinking of how spatial matter was determined in a critical form. This change of thinking occurred in three forms: ontologically, sociologically, and the combination of this socio-spatial dialect. Together the aim shifted to be able to measure what matters in a socio-spatial context.

- Black Lives Matter (Ferguson) - The Black Lives Matter movement challenged design thinking because it emphasized the injustices and inequities suffered by people of color in urban space, as well as emphasized their right to public space without discrimination and brutality. It claims that minority groups lack certain spatial privileges, and that this deficiency can result in matters of life and death. In order to reach an equitable state of urbanism, there needs to be equal identification of socio-economic lives within our urban scapes.

Comments

Post a Comment